The Making

of a QAnon

Content Warning: Mentions of pedophilia, racism, sexual assault, anti-Semitism

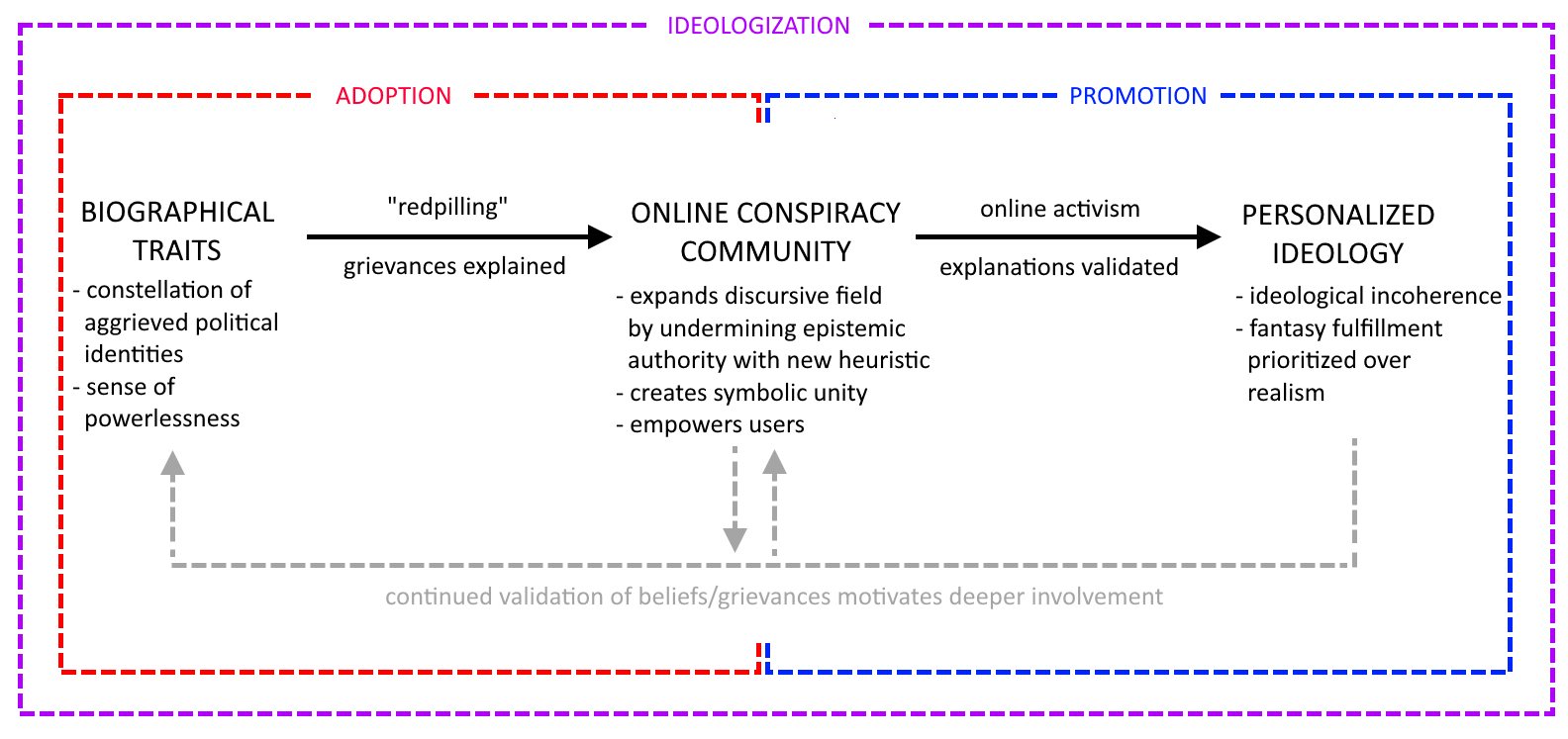

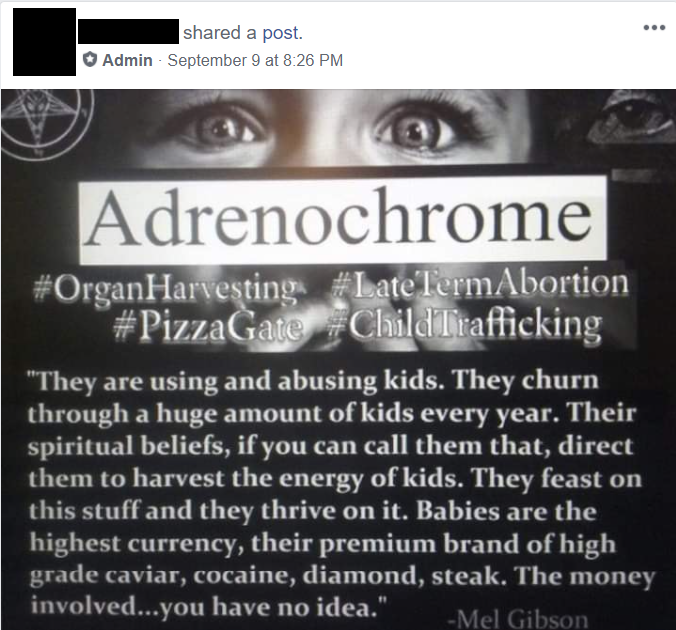

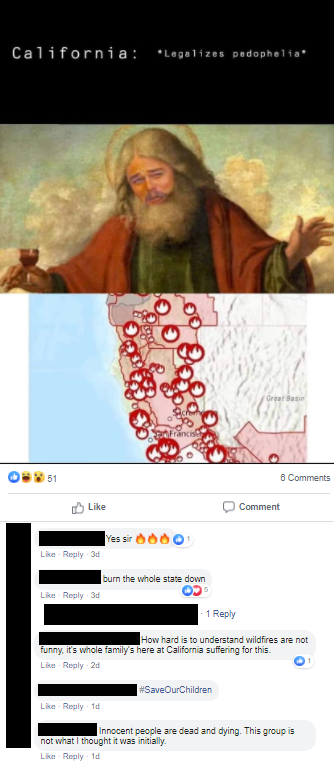

Conspiracy theories are endemic to American culture. Ranging from the (mostly) harmless theories about a faked moon landing or gay frogs to the unsettling stories about pizza parlor-based child trafficking, these conspiracy theories shape American public discourse and culture. Not all conspiracy theories are made equally: some are grounded in actual government programs intended to manipulate media or disrupt movements for racial justice, while others are as factual as the Earth is flat. They may be large, determining a person’s entire worldview or political ideology, and they may be small, casually believed as a simple, unspoken fact of the world.

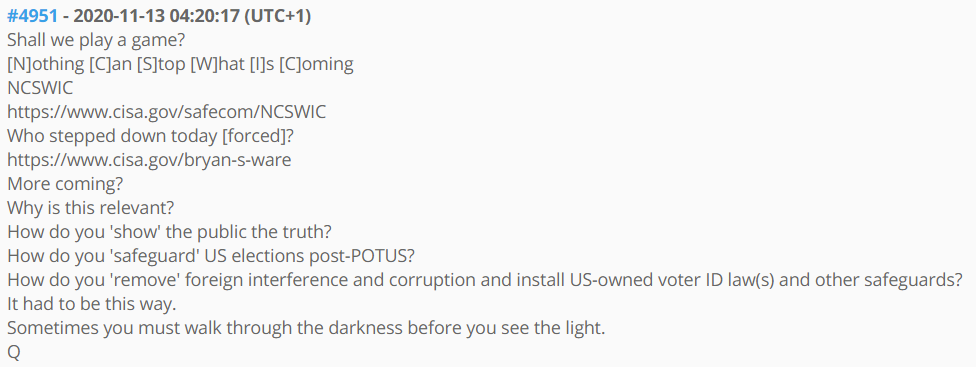

Still, at the heart of every conspiracy theory are conspiracy theorists, the people tirelessly working to make the “truth” known. This group of people are hard to characterize because they are just as diverse as the wide-ranging theories they imbibe. However—despite provocations to do otherwise—many people home in on the most outlandish of conspiracy theories and resort to describing their adherents in victimizing, pathologizing, unsympathetic terms. A prime example is the latest and largest American conspiracy theory, QAnon, which asserts that a Satanic, pedophilic cabal of political elites have taken over the government. In this theory, Q—an anonymous military operative—is distributing coded messages to assist former president Donald Trump in his overthrow of the cabal. Sounds…crazy, right?

“Crazy” might sometimes be an accurate characterization of followers’ beliefs—and maybe even followers themselves—but more often than not, it’s an oversimplified understanding of both what supporters believe and why they believe it. In this brief, interactive version of my undergraduate thesis, we’ll look at how regular people come to believe in QAnon and end up promoting it to a wider audience, before quickly looking at the effects of these dearly held beliefs. So let’s jump in.